What do I mean by the title? I'm one of those guys who never figured out WTF I was supposed to be doing with my life. That line by Rodger Hodgson in his last album with Supertramp always sticks in my mind:

|

| End of year 2024 |

|

| Early 2025 |

What do I mean by the title? I'm one of those guys who never figured out WTF I was supposed to be doing with my life. That line by Rodger Hodgson in his last album with Supertramp always sticks in my mind:

|

| End of year 2024 |

|

| Early 2025 |

|

| Balboa Park, much as it's always been at holiday time |

|

| Day before Xmas 2024 in Borrego Springs (yeah, a year ago) |

A Prelude

Approaching age 68, my desire either to express myself creatively or to try to change the world has diminished considerably. A motorcycle accident during a routine ride around town in March left me with serious injuries that will limit my physical capabilities for the rest of my days, and the state of the world over the past couple of years just keeps me in a state of borderline despair usually manifested as apathy. I move between San Diego, my acreage in Prescott, and my small condo in Miami Beach, doing pretty much the same thing in each place.

In Prescott recently for five weeks, I followed a series on the NBC Phoenix outlet about the ongoing drought in the Southwest. Lake Powell is drying up, and Lake Meade, fed by it, is at such a low level that there is danger of it no longer being able to generate hydroelectricity. Builders continue building, investors keep on investing, people keep going about their wasteful ways perhaps because the catastrophic reality of this situation is too grim to contemplate. "Conservatives," for lack of a better label, continue to insist that there isn't enough evidence to warrant drastic action, even though they seem to think it's a fine idea whenever the U.S. invades another country and kills several tens of thousands of noncombatants because they think the country maybe, possibly was harboring weapons of mass destruction. Doing anything proactive about climate change though--just in case--is the stuff of wacky muddleheadedness.

When it all goes dry and life is no longer sustainable, these same A-holes will screw up their faces and claim there was no way of knowing this would eventually happen. They'll call the forward-thinkers a bunch of screwball liberals, fume that there's no point in placing blame about the past now, and look about for someone else to invade so that we can acquire the resources necessary to "preserve our way of life." This time, however, with the climate no longer cooperating, one wonders if there will be any way of life left to preserve.

A Prequel

I was a kid of the 1960s, more an observer than an active participant, and barely 15 years old when the 1970s started. I turned 8 in December of 1962, was just learning to read with any amount of comprehension any sort of publications like San Diego's Evening Tribune, Life Magazine, or Readers Digest, all of which my parents subscribed to. I couldn't have identified many celebrities other than Johnny Downs, the former Our Gang member who hosted the after school cartoon program in San Diego, and perhaps Walter Cronkite, who always made me uneasy because he was on TV every damned night talking about natural disasters and various crummy things that had happened in the world that day.

It's fun now, as a much older adult, to review some of the news stories of the time that I was too young to truly understand, and to read about the history of places that were just vague names in the news then, but places I've visited and come to know since.

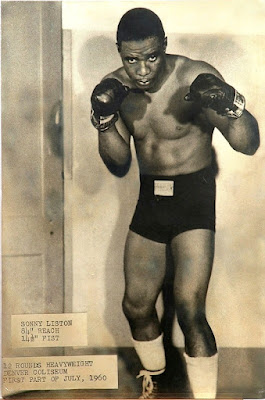

Sitting back in Prescott by myself in the evenings, hearing and reading about Lake Meade, I began looking up little factoids about Las Vegas. Coincidentally, I've been getting a lot of recommendations about boxing history sites sent my way on the newsfeed of my social media. In that way did I get to thinking about a celebrity from my childhood, the world heavyweight boxing champion from 1962 to early 1964, Sonny Liston.

A Man

Liston is interred in a cemetery along the flight path of what was until very recently known as McCarren International Airport in Las Vegas, with the simple inscription on his headstone of "A Man." The site has occasional visitors who seek out his final resting place, but fewer and fewer as time passes. His life is a bit of an enigma, not least because no one is really sure of either the date and year of his birth, or the exact date and cause of his death in his Las Vegas home during the holiday season of 1970.

He was, in a sense, the champion nobody wanted. Born poor to a sharecropper family in Arkansas, put to work in the fields at an early age, and beaten incessantly by his father, in his early teenage years he shook the fruit from a tree, sold it, and made his way 300 miles north to St. Louis to find his mother, who had relocated there to seek factory work. Big and exceptionally strong for his age, he tried going to school but was ridiculed for his complete lack of literacy or prior education. He tried to make an honest living, but the only employment available was unskilled and low paying.

The young man turned to petty crime, leading a small gang in muggings and armed robberies, becoming well-known to local police. In time, he was arrested and sent to Missouri State Penitentiary. Liston never complained about prison life, finding it the only place he'd known where he was guaranteed three meals a day. A Catholic priest in charge of the prison's athletic program suggested that he take up boxing. With his exceptionally long reach, large fists, and natural talent, he soon excelled to the point that he obtained an early release on the condition that he have a sponsor for an amateur career.

Prison officials were not happy with the sponsors who came forward, with their connections to organized crime, but thought it a better solution than keeping Liston in prison. Thus did Liston's future lifelong connections with the mob begin. While boxing as an amateur, he did additional odd jobs for them as an enforcer and debt collector. Inevitably, he became known as a "usual suspect" among the St. Louis police, and this marked also the beginning of his lifelong negative encounters with law enforcement.

He moved later to Philadelphia, but fared no better. Perhaps tired of being harassed, he at one point beat an officer unconscious and took his gun, for which he earned more jail time. By now he was earning a fair amount as a professional boxer, and had little need to commit petty crime. It is difficult to know to what extent these problems were of his own making, and to what extent he was unfairly profiled and targeted. There was the stigma of his mob connections, but there was also the context of the pre-civil rights era that he came of age in. Targeting a black male unfairly, particularly one who was becoming reasonably successful in his profession, did not arouse the widespread sympathy or indignation of the public that it would today.

None of the alleged infractions for which he was targeted were particularly egregious, but they gave him the reputation of a troublemaker as he moved up the professional ranks. By the time he reached first rank status and talk of taking on Floyd Patterson for the heavyweight championship became serious, the NAACP and eventually President John Kennedy himself were urging Patterson not to accept the challenge. Cus D'Amato, Patterson's trainer and much later in life the mentor and father figure to Mike Tyson, personally opposed the match due to Liston's troublesome connections. The fight was finally arranged, however, and Liston walloped Patterson in the first round to become the heavyweight champion of the world.

The champion's crown was always an awkward fit for Liston, and for the entire nation. He was seen as a poor role model, unworthy of the prestigious title. He vowed to do his best to be worthy, but was deeply disappointed when he returned to Philadelphia and found virtually no one at the airport to welcome him. Nonetheless, tutored by his wife, he learned to sign autographs with simple messages, and to read everyday signage and advertisements. Advised by Joe Louis, a close companion, he mastered the basics of being a public relations-conscious celebrity. By nature, he had a rapport with children and the elderly, perhaps because he felt they were the only people who had no designs on him and wanted nothing more than to meet him and shake his massive hand.

It has been argued that Liston, rather than Muhammed Ali, was the first civil rights era heavyweight champion. Ironically perhaps, through his mob connections he was accustomed to dealing with white people in a matter-of-fact, businesslike way. He was nonpolitical and noncommittal about the movement, participating only in a single demonstration with civil rights leaders against a church arson. After living briefly in Denver, the mob helped him purchase a house in an all white neighborhood on a golf course in Las Vegas. Despite the initial concerns of neighbors, he proved to be an affable family man, and remained there for the rest of his life. He made goodwill trips as champion, posing in a kilt and attempting to play the bagpipes in Scotland. He was persuaded to pose for a famous December 1962 magazine cover while wearing a Santa cap.

By the time he was challenged by Cassius Clay--later Muhammed Ali--in February 1964, he had gained at least tolerance by the public. Although Clay trained regularly at the 5th Street Gym in Miami Beach, he was not permitted to stay overnight during the buildup to their fight there. Hampton House, a well-known stopping place for black celebrities across the causeway near Liberty City, provided his accommodations. Liston, meanwhile, was a guest at the Casablanca in the north part of the city, as an apparent exception to Jim Crow laws in the final months before the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Beatles were in town, taping their second Ed Sullivan Show appearance at the nearby Deauville, and Liston was in the studio audience with Joe Louis. Neither expressed any great interest to meet them, but the Beatles would later visit the 5th Street Gym and have a famous photo op with the man who would soon dethrone Liston.

The rest of the story is a bit sad. Liston did not train diligently for his first fight with Clay, and was TKO'ed in seven rounds, perhaps disabled by an injured shoulder. He trained even less for their second meeting the next year, being felled by the famous "phantom punch" in the first round. It is widely believed that he threw the fight, and there is much speculation as to why. Pressured by the mob, threatened by the Black Muslims who favored the man now known as Muhammed Ali, never truly comfortable as the champ, perhaps he just figured he'd had enough. He had a nice house and a comfortable life. Perhaps, as in Rocky III, he'd become complacent and Ali served as his Clubber Lang, though unlike Rocky, he exhibited no great determination to redeem himself.

As a kid, I recall reading that he'd been arrested not long afterward in Vegas for a concealed weapon violation. My sense was that his life was going downhill. His wife Geraldine would say later that every negative encounter he had with the police in the time she had known him began with a round of drinking, which he apparently liked to do often. Still, he lived a relatively quiet life for his final five years. Like too many boxers past their prime, he attempted a comeback in the late 1960s with some success, but was also beaten a time or two. By 1970, he was almost forty years old, perhaps more, and neither enthusiastic nor agile as a fighter.

Geraldine returned from a holiday visit to St. Louis in early 1971 to find Sonny dead. The cause has always been something of a mystery, and the exact date of his death, like that of his birth, will never be known with certainty. He'd won the last bout of his comeback a few weeks before, and it has been speculate4d that he'd been told to take a fall. Perhaps it was a final act of defiance, an assertion of his independence, that led him to be murdered. Perhaps he'd actually suffered a heart attack at home alone, and was unable to seek help.

An Era

Liston's passing was not widely noted by the media in early 1971, just a couple of months before Muhammed Ali would challenge Joe Frazier the first time for the championship. Ali would lose that one, but as we know it was far from the end of his career, which had been detoured for three years after he refused induction into the armed forces at the height of the Vietnam War. He would regain the heavyweight championship more than any other, and become a living legend. His first loss to Ken Norton in 1973 was widely believed to be the end for him, but he apparently saw it as comparable to his 1964 defeat of Liston, where his opponent had not taken him very seriously and showed up to fight in less than his best condition. Never again would Ali enter the ring less than thoroughly trained.

Later in life, Ali would express sympathy for his old nemesis. He felt that there was a dark moodiness about Liston, a sense of a man who'd had it rough, seldom seemed to catch a lucky break, and dealt with life's setbacks in his stoic way. He was not the only one to feel that, in retrospect, Liston was a more complicated and intriguing character than the man portrayed by the media.

Comparisons to other boxers, or other eras, have limited usefulness. Liston was in some ways a transitional figure in the transitional era of the early 1960s. By circumstance, he was concerned primarily with his own wellbeing rather than with the social change going on around him. He was independent minded, yet beholden to powerful others who always loomed large in his consciousness. The tone of his life and times has more the feel--the brooding darkness--of the Godfather movies than the good-guys-always-win aura of the Rocky series. The public expected much from the heavyweight champion of the world in those days, and never more than in the nascent civil rights era. Liston made some efforts to live up to those expectations, with encouragement and advice from Joe Louis. In the end, however, his unsavory connections and run-ins with the law limited his ability to polish his public image.

Mike Tyson, who admired him greatly and was sometimes compared to him, provides an interesting study in contrasts. Liston was about a decade older when he reached the top, more seasoned by life, and less overwhelmed by sudden fame and fortune. His mentors had been mobsters, who saw him more as a useful commodity than as a talent to be nurtured, He never had a true caring mentor, a Cus D'Amato of his own, Though many admired him quietly, he also never had a true fan base as a celebrity... nor did he seem to seek one. By the time he became champion, he had been married for a time and had a stable home life quite incongruous with his public image. The limited literacy Liston attained was through the efforts of his wife, as government in the era he grew up and in remote rural areas especially, had little interest in providing its citizens with a basic education,

Given the relatively benevolent option of reform school in his youth, it is hard to know how Liston might have developed. He was, by all accounts, a bright and perceptive individual. Like Tyson, and like all people of exceptional attainments, he had that special intelligence that enabled him to direct his talents toward greatness. One has to admire, even wonder, at the tenacity of a boy barely thirteen years old making his way to St. Louis, illiterate, with no sense of geography, little understanding of money, and no experiences outside the rural environment where he was born. Never seeming to catch a break, perhaps the luckiest twist in his life was going to prison and discovering boxing.

McCarran International Airport, named for a former Nevada politician with notoriously unenlightened views on certain ethnic groups, was renamed for Senator Harry Reid around the time of the latter's passing. Planes still pass over the otherwise peaceful cemetery on a regular basis. The gravesite is not well known, but has occasional visitors. One has to wonder, hearing the roar of jet engines, considering the work and effort it takes to keep a fleet of airliners moving toward their destinations, and thinking of all the people aboard those planes--coming and going for various purposes--whether a small part of all that energy and life force might periodically mingle with the desert sunlight and through some cosmic mix produce a positive vibe over the final resting place of Charles "Sonny" Liston, A Man.

|

| Never truly loved or esteemed even as the champ, Liston nonetheless was not without a sense of public relations and good nature.. |

|

| In publicity photos, to my young mind he appeared more impassive and intense than angry and menacing. |

|

| The famous December 1962 magazine cover |

|

| During changing times, Liston's opponent for the February 1964 title fight met the Beatles at the 5th Street Gym in Miami Beach. |

It's cliched to say that 2020 sucked. In a global sense, sure, but for me it really wasn't that much of an Anus Horribilius or whatever the fancy term is. I retired in December 2019, a couple of days after turning 65, headed out to Miami Beach for a few weeks, then took a cruise back to San Diego through the Panama Canal. About a month later, the whole world shut down while I was on a planned week-or-so trip to Prescott with little more than a change of clothes. I was there until early May, then back in San Diego in time to see downtown La Mesa burn just after Memorial Day. At the end of June, some tweaker-of-color tried to break into my condo at 3:30 AM, and I have very little doubt that his addled brain was emboldened by the zeitgeist. I would be back out to Prescott two more times, and Miami Beach again for the first time since the beginning of the year for a few weeks in mid-September/early-October.

Before you knew it, the year was at an end again, and here I am back in Miami Beach for a month. It's been pretty phenomenally lazy, a year into retirement and now accustomed to not really having to do much of anything I don't feel like doing. Social life for most people has come to a standstill, but it doesn't bother me that much because my social life was always more or less at a standstill. I listen to discussions on TV about teenage pregnancy, abusive relationships, and such problems, and can't comprehend such things really. It's been eons since any female gave me the smallest opportunity to get her pregnant or abuse her, even if I wanted to. It seems the whole world, in the first year of my retirement, has been modified to reflect the lifestyle of yours truly.

Financially, it's been a challenge. I was planning on depending largely on my rental income in retirement, then the virus started affecting tenants' ability to pay rent. On top of that, there were two extremely expensive tenant turnovers, one coming right after I thought I was recovering from the other, and totaling $45,000 in repairs and expenses by fall. My smaller, simpler place in Yuma also had almost monthly nagging expenses, appliances going out and such. I spent most of August in San Diego working on one of the places myself, but it still was draining my savings at an alarming rate.

On top of all this, I'd put a metal roof on the Prescott place in December and replaced the oak crown moldings inside that the painters had F'ed up and painted over before the final tenancy, only to find I had a pack rat infestation under the house on coming out to see it. I battled it myself with little help from a basically useless pest control company. Then in March, my neighbor to the east finally put his vacant lot up for sale. Clobbered and reeling from expenses, I nonetheless realized that the chance would never come again and managed to cobble together the money to buy it from him by cashing in part of my Roth IRA and dipping for the first time into my equity line of credit.

Each time I think I'm getting some breathing space, another calamity comes up, so I'm not going to say I'm out of the woods yet. Buying the neighbor's lot, though, was the culmination of a 20+ year old dream; it was just crappy timing is all. Thus, I'll say that as of early January 2021, life is all right.

|

| Prescott, Spring 2020. The news on the single antenna station I got there was relentlessly bad, but breakfast was always a peaceful if lonely ritual. |

|

| Early in the March thru May stay, looking east toward my newly acquired acreage and dreaming of better days. |

|

| With plenty of time for such things, my stone lantern got an uplift after tenants had spent over 20 years shooting at it and such. |

|

| Back in San Diego in late summer, taking a break from endless work on the back unit of my duplex, a mid-year unexpected mega-expense. |

|

| Early October, on return from 3 weeks in Miami Beach. Kinda the epitome of what it is to be retired and just not give much of a shit. |

|

| During the fall return to Miami Beach. Same pose; different location. |

|

| Home-cooked pork with black beans and a nice Cuba Libre in Miami Beach, September 2020. |

|

| Prescott |

|

| San Diego |

|

| Miami Beach |

|

| SDSU Donor Wall, with the oldest man in the world |

|

| Teachers' conference in Sacramento early this year. Oldest man in the world back and center. |

|

| Hangout of the oldest man in the world |